Amina Zarrugh, Ph.D., is an associate professor of sociology at Texas Christian University and a 2023-2024 PRRI Public Fellow. Her research areas are immigration and migration.

During the 2024 presidential election primaries, the notion of “birtherism” again made the headlines in American political discourse. Frequently invoked by former President Donald Trump in the years prior to his running for presidential office in 2016, “birtherism” refers to the organized effort to sow suspicion that an individual running for political office was not born in the United States and is therefore not eligible serve as president of the United States. “Birtherism” coalesced into a social movement around 2008, organized to instill doubt among the American public as to whether then-candidate Barack Obama was born in the United States. Research suggests that such skepticism about Obama’s birth was particularly embraced among highly educated and “racially conservative” white Republicans.

Over a decade and a half later, Republicans once again appealed to “birtherism” to raise questions about the pursuit of the Republican presidential nomination by former governor of South Carolina, Nikki Haley, whose parents were born in India. Similar “birtherism” was also employed a few years ago to foster doubt about the eligibility of U. S. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas and Vice President Kamala Harris when they were running to become president. While the “birther” movement is not embraced in all corners of the Republican Party, questions of birth and who can exercise particular civil rights have been raised by multiple Republican candidates running for public office in recent months, focusing most squarely on birthright citizenship.

The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1868, extends citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” The amendment is widely interpreted as enshrining “birthright citizenship” as a fundamental aspect of naturalization policy in the United States. Birthright citizenship, specifically for children of undocumented immigrants, was opposed by several candidates seeking the Republican nomination for president in the last year and has been the subject of publications by conservative think tanks, such as the Heritage Foundation.

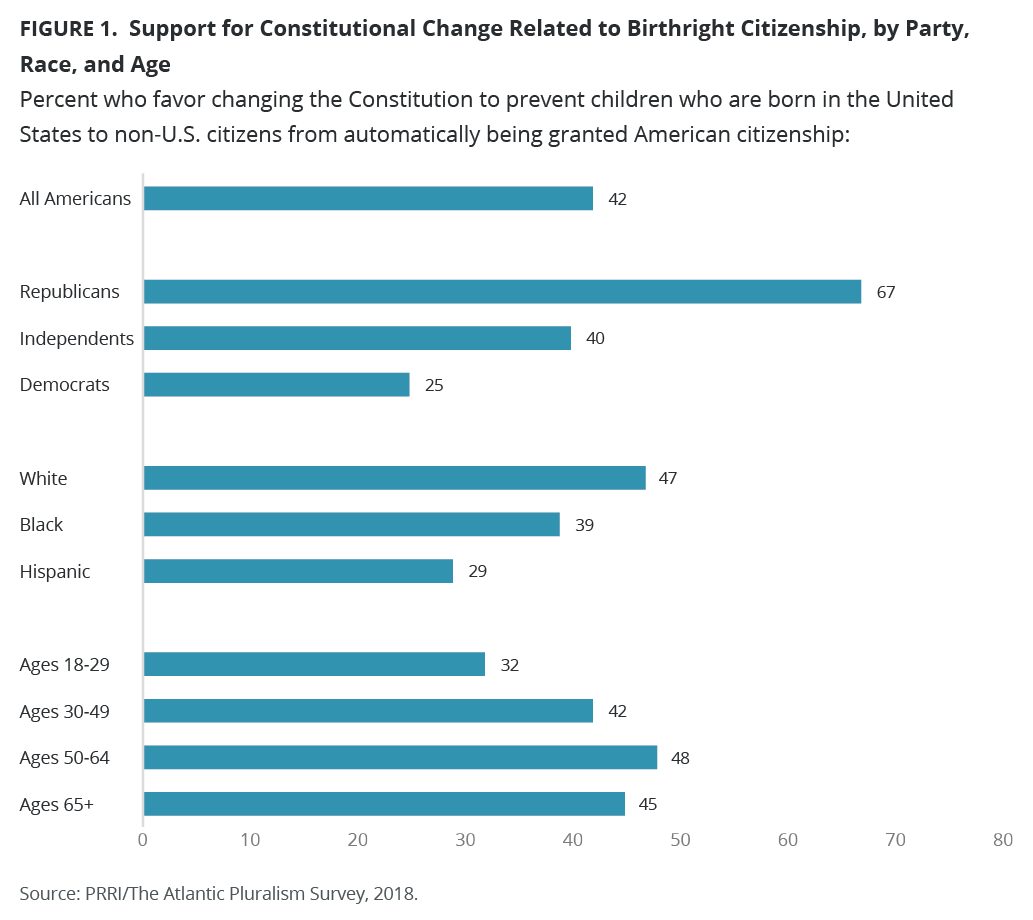

Fundamental changes to the policy of birthright citizenship, however, are not supported by the majority of the American public. In PRRI’s 2018 Pluralism Survey (conducted with The Atlantic), only 42% of respondents said that they would favor or strongly favor changing the Constitution to prevent children who are born in the United States to non-U.S. citizens from being granted citizenship. Notably, 67% of respondents who identify as Republican favored or strongly favored a constitutional change related to birthright citizenship, which is significantly higher than the 40% of independents and the 25% of Democrats who favored or strongly favored a constitutional change.

Considerable differences in opinion about a constitutional change also emerged across racial, ethnic, and age groups. Nearly half (47%) of white Americans favored or strongly favored a change to the Constitution compared to 39% of Black Americans and only 29% of Hispanic Americans. In terms of age, respondents ages 18 to 29 were least likely to favor or strongly favor a constitutional change to limit birthright citizenship (32%), compared with 42% of those ages 30 to 49 and nearly half of those ages 50 to 64 (48%) and over the age of 65 (45%).

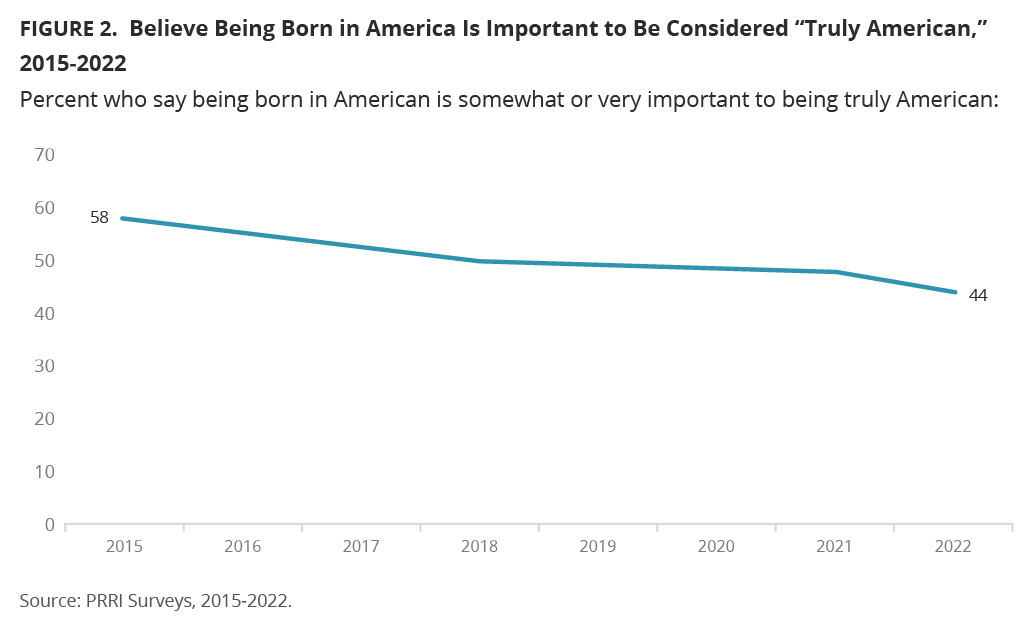

Furthermore, while the connection between birth and the meaning of being American remains salient in American culture, its importance to Americans has declined in recent years. In multiple PRRI surveys between 2015 and 2022, respondents were asked about the extent to which being born in America is important in order to be considered “truly American.” In 2015 and 2018, over half of Americans (58% and 50%, respectively) regarded being born in the United States as somewhat or very important in order to be considered truly American. In 2021 and 2022, the percentage of respondents who shared this sentiment declined slightly to 48% and 44%, respectively.

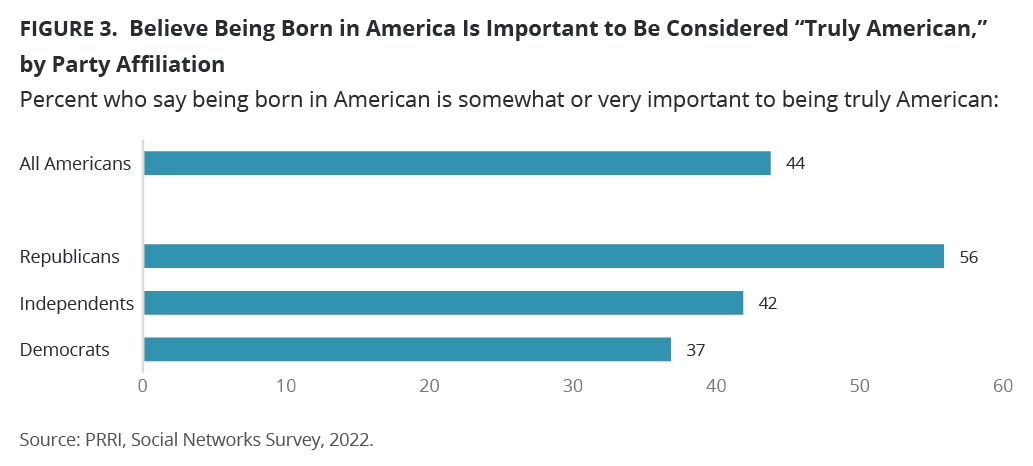

In PRRI’s 2022 Social Networks report, the most recent survey to pose this question, significant differences in perceptions of the importance of being born in the United States emerge across political affiliations. In fact, 56% of Republicans regard it as somewhat or very important that someone is born in the United States to be considered “truly American” compared with only 37% of Democrats.

Collectively, PRRI data about birthright citizenship and the importance of being born in the United States expose some interesting contradictions. Just as Republicans are significantly more likely to emphasize the importance of being born in the United States to be considered “truly American,” they are also more likely to support measures that limit access to citizenship based on birth, at least for the children of non-U.S. citizens. The picture that emerges is one in which being born in the United States confers to someone the status of being “truly American” – and the ability to enjoy civil rights associated with citizenship – only if one’s parents were already U.S. citizens. This logic undergirds “jus sanguinis” or “right of blood” citizenship policy, which confers citizenship on the basis of blood lineage and can give way to more ethno-nationalist, exclusionary forms of citizenship. These patterns also help us understand the ongoing appeal of “birtherism” conspiracy theories on the right, which have targeted politicians of color whose parents migrated to the United States from non-European countries.